Please contact Bryars & Bryars if you have any old photographs, memorabilia or recollections about Cecil Court which you would be happy to share, or if you spot any literary references to the street. This is a work in progress and a great deal of information is still emerging. For the twentieth century the memories of booksellers – and other shopkeepers - and their customers are especially important.

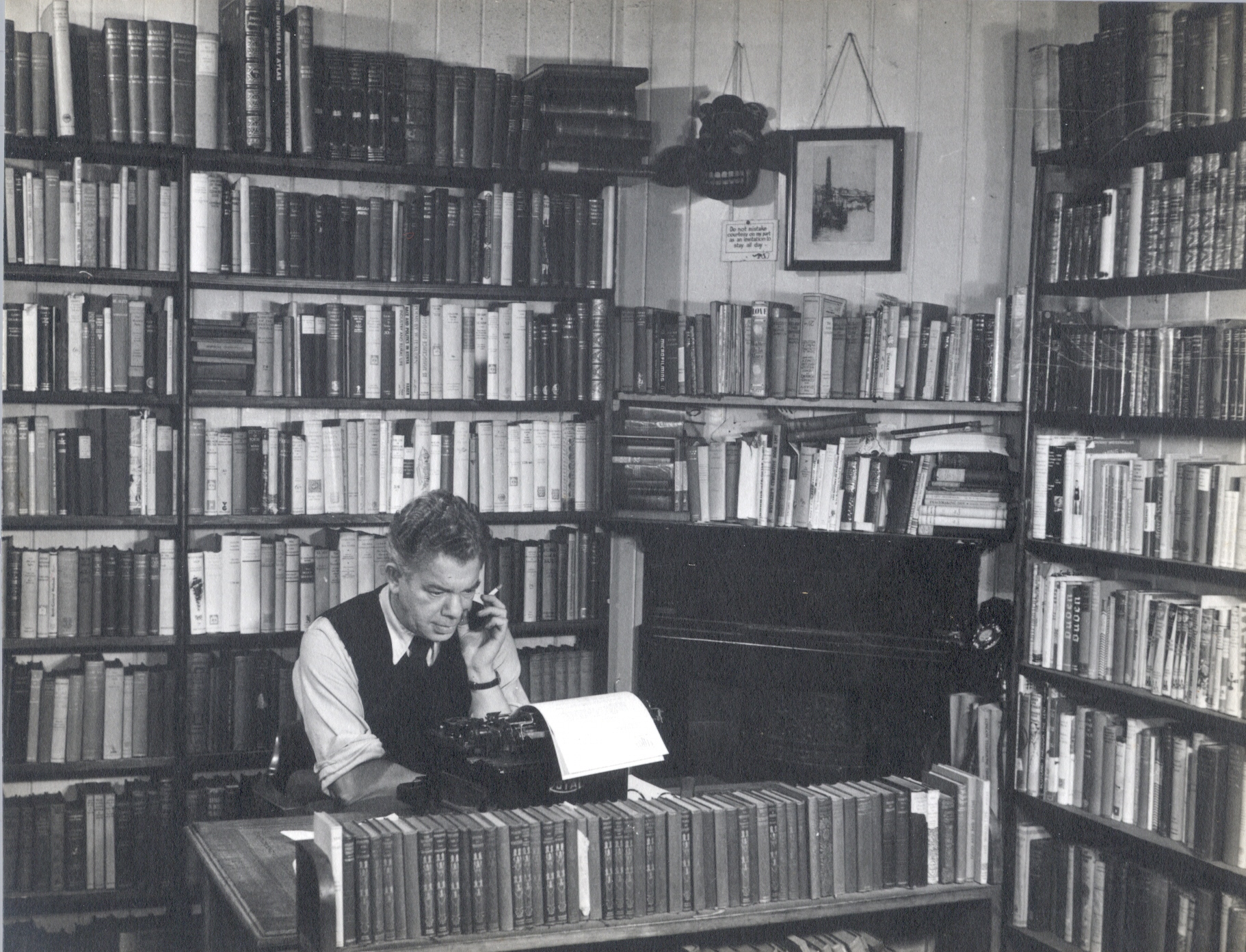

Bob Chris on the telephone in 8 Cecil Court, probably in the 1950s. The sign pinned to the wall above the mantelpiece reads: ‘Do not mistake courtesy on my part as an invitation to stay all day’

The eternal tread of feet upon the pavement

Dickens’ “eternal tread” could apply to any London street, but is especially true of a place like Cecil Court. Located in the heart of Theatreland, Cecil Court is a matter of a few yards from the cinemas of Leicester Square, close to the Coliseum and Royal Opera House, the boutiques of Covent Garden and galleries of Trafalgar Square, and it is only a few minutes’ walk from Parliament in one direction and the Royal Courts in another. Actors, lawyers and politicians mingle with tour groups, and there’s no reason to suppose that the mix of humanity has ever been greatly different, or any less interesting.

It doesn’t take any great leap of imagination to picture Hogarth using Cecil Court as a shortcut between his house in Leicester Square and his Academy in St Martin’s Lane, or Johnson and Boswell hurrying the other way, from Old Slaughter’s Coffee House to a meeting of the Club on Gerrard Street. On Tuesdays, in the years before the First World War, a group of poets including W.H. Davies, Rupert Brooke, Edward Thomas, Walter de la Mare, and Robert Frost would lunch at Mont Blanc restaurant on Gerrard Street before taking tea at St George’s Café on St Martin’s Lane, adjacent to the Coliseum: a gaggle of far from starving poets could have been a regular Tuesday sight for the shopkeepers of Cecil Court, as they passed through.

All this has to remain supposition (at least until I find a letter from Brooke mentioning that he stopped en route at Brightwell & Co, the military tailor then at number 24, to order a new tunic or half a dozen shirts …) but fortunately for us an extraordinary array of people have left evidence of more tangible associations with Cecil Court. It was the first London address of W.A. Mozart and his family, arguably where he composed his first symphony; film pioneers such as James Williamson and Cecil Hepworth regarded ‘Flicker Alley’ as the heart of the early British film trade; a young Arthur Ransome honed his writing skills while doing as little work as possible for Ernest Oldmeadow at the Unicorn Press; long-term residents of the flats above Cecil Court include T.S. Eliot and actors such as Ellen Terry, and patrons of the shops below range from Aleister Crowley to Graham Greene, by way of T.E. Lawrence. Then there are the ordinary residents of Cecil Court – not necessarily famous but often remarkably interesting – including coiners, arsonists and radical atheists; finally there are the booksellers who have made Cecil Court their own, beginning with John Watkins and the brothers William and Gilbert Foyle in the earliest years of the twentieth century.

Cecil Court Begins

Cecil Court was laid out in the late seventeenth-century, filling in open land between St Martin’s Lane and Leicester Square as London spread steadily west. It is still owned by the family from which it takes it name, the Cecil family of Hatfield House in Hertfordshire, who are the descendants of Robert Cecil, created first Earl of Salisbury by James I after he smoothed over the transition from the house of Tudor to that of the Stuarts. A protégé of Sir Francis Walsingham, Cecil had been trained by him in matters of spycraft as well as statesmanship, and as Secretary of State for both Elizabeth I and James I he was deeply involved in matters of state security. The land on which Cecil Court now stands was purchased in 1609, in Cecil’s lifetime, and it is one of a number of nearby streets and places that have since been named for the land-owning family including both Cranbourn Street and the Salisbury pub on St Martin’s Lane. A sketch-plan of ‘St Martin’s Field’ as it then was can be found in the Survey of London. Cecil Court would be built on a five acre tract formerly known as Beaumont’s lands.

Cecil Court is generally thought to have been laid out in the 1670s (for example by Gillian Bebbington in ‘Street Names of London’, 1972). However, it does not appear on William Morgan’s extraordinarily detailed 1682 map, ‘London &c. Actually Survey’d’ and does not appear in the rate books until 1695 – although that does not prove that it did not exist before. Cecil Court’s outline can be found on later maps – most clearly on Richard Horwood’s map of 1799 which was the first to show individual house numbers. The only known illustration from that period is from an eighteenth century advertisement for Kendrick’s bootmakers, which includes a woodcut depiction of the shop’s interior accompanied by the legend:

“There lives a man in Cecil Court / Where all the bucks and beaus resort / In Cordovian taste so neat / To grace their handsome legs and feet”.

However, two watercolours painted shortly before Cecil Court’s redevelopment of 1889-1894 are held in local archives. The first is in the London Metropolitan Archives, printed in volume 20 of the Survey of London (1940). Painted by J.P. Emslie in 1883 it shows the south side of Cecil Court, but while the architectural details are interesting the perspective is quite misleading: it appears to have been painted from a vantage point set well back from the picturesque shop-fronts, from across a broad piazza, quite impossible in the narrow confines of Cecil Court!

Goodwin’s Court, autumn 2007

The second picture of Cecil Court, signed F. Calvert and dated 1892 (which means that it must have been painted immediately prior to demolition), can be found in Westminster Archives and gives a better impression of how Cecil Court would have looked to a casual observer, in this case standing at the Charing Cross Road end. Nothing at all of the fabric of these buildings survives, as I’ll explain later, but for the modern visitor to the area I’d suggest that Goodwin’s Court, on the opposite side of St Martin’s Lane (entered through a narrow passageway which is easily missed, and largely unaltered) is the best place to get a feel for the atmosphere of Georgian and Victorian Cecil Court.

The earliest description of the street we have is from John Strype’s “Survey of the Cities of London & Westminster” (a thoroughgoing revision and expansion of Stow’s much earlier Survey) which was published in 1720: “First St. Martin's Court, a large handsome Court, with good new built Houses, and a Free-stone Pavement, having a Passage into Castle-street; and in the Midst it hath an open Square, at the End of which there is another Passage into Castle-street. Cecil-Court also a new built Court, with very good Houses, fit for good Inhabitants, and hath a large Passage, with a Freestone Pavement, into Castle-street, and out of this Court is a Passage into St. Martin's Court.” The whole of this tremendously useful work is now available online thanks to the Stuart London Project.

Cecil Court: In Trouble & On Fire

Cecil Court may have been “fit for good inhabitants” but we have good reason to suppose that eighteenth century Cecil Court was not an especially salubrious address. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey give an insight into life in the street at the time, whenever the inhabitants fell foul of the law. Residents crop up regularly in the trial transcripts, mostly for petty theft but also for highway robbery, forgery and arson. In 1735 Elizabeth Calloway, keeper of a Brandy Shop in Cecil Court where her clientele could be found “drinking, smoaking, and swearing, and running up and down Stairs till one or two in the Morning” seemingly over-insured her goods and set the place alight. Her neighbours’ houses were also burned to the ground while she sat smoking her pipe and drinking good Sussex beer with friends a few streets away. Calloway’s poor lodgers - the widow Feltham, her daughter and young grandson who rented the cellar - fortunately escaped with their lives just as their ceiling collapsed (Calloway had offered to take them out and ‘treat’ them, but they rejected this uncharacteristic offer). Various witnesses gave evidence that her storeroom was empty and, on rescuing barrels from the fire (presumably expecting them to be full of spirits) discovered that they were empty too. The blaze could have been started by the heat from the cook’s shop next door (kept by Eleanor Pickhaver, accused by Calloway of selling ‘sandy’ boiled beef), or the bundles of kindling purchased by Mrs Calloway a fortnight before the fire might have had a sinister purpose. The jury was inclined to acquit.

The Cecil Court fire rates a mention in later Victorian and Edwardian histories of London – particularly if the author was finding a way through the capital street by street. Mrs Calloway may have been acquitted by a jury of her peers, but subsequent commentators have been less generous. Austin Dobson, for example, recounts how, having been served with a notice to quit, Calloway resolved to “warm all her rascally neighbours”. (Austin Dobson, Miscellanies (1901) p. 47). It has the ring of a sensational contemporary account, but certainly wasn’t derived from the trial record.

Other residents of the Court went on a spree of looting under cover of the flames. Mary Steward alias Young (a poor cellar dweller like the Felthams), ‘accidentally’ took in a bed and three pictures from one of the burning houses “in the hurry and fright she was in”, allegedly mistaking them for her own. The jury acquitted her too (perhaps because a conviction would have invoked the death penalty), and also acquitted Eleanor Newby, who ‘assisted’ her former employer by removing six curtains and five China Dishes from his house during the fire, which were subsequently discovered at her lodgings; however, James Newby was transported for stealing iron bars and an iron pin from a press valued – for the purposes of the court – at 18d. The thieving didn’t stop with the fire itself. William Gordon and his wife were burnt out by the fire, and took lodgings in Cranbourn Alley, where they were robbed by their servant. Again, although the goods were found on her person she was acquitted.

The fire spread to neighbouring St Martin’s Court, where a further 15 houses were destroyed (as opposed to three in Cecil Court itself). The “Daily Journal” of June 11th described how the fire “continued with great Fury for the Space of two Hours before water could be got to supply the Engines. His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, the Lord James Cavendish, Sir Thomas Hobby, and Mr Cornwallis were present; a detachment of Foot Guards also assisted: His Royal Highness went of top of a house in St Martin’s-Court to take a View of it, and the came down to direct the Engines, and animate the Firemen & c.”. (Prince Frederick held court a few hundred yards from the flames at Leicester House on the north side of Leicester Square; he predeceased his father but his son became George III).

The only person known to have died as a result of the fire was the mother of the painter William Hogarth: the unfortunate lady died the following morning “at her house in Cranbourn-Alley, of a Fright, occasion’d by the Fire in St Martin’s Court. She was in perfect Health when the unhappy Accident broke out, and died before it was Extinguish’d”. See Ronald Paulson: “Hogarth: High Art and Low 1732-1750” (1992) p. 54.

Cecil Court crops up again and again in the Old Bailey trial records in alibis (at his trial in 1770 Benjamin Jones claimed that he couldn’t possibly have been committing highway robbery as he was drinking and conversing with some ladies in Cecil Court at the time of the offence; his alibi was not accepted by the court and he was sentenced to death) and occasionally takes centre-stage as the scene of the crime. The pick pocketing of a watch in 1779, in a house of ill repute known as the Ham, is fairly typical. William Stonehouse, apothecary, out for a night on the town with a gentleman friend and already “a little elevated” was accosted by two women who asked for wine and led them to the Ham in Cecil Court. In common with other public houses which crop up in the trial reports, there was a room for ‘company’ and several private rooms. They called for wine and water and Stonehouse’s friend retired briefly with one of the ladies. When he emerged he made his way home without further comment, leaving Stonehouse cosily flanked by ladies of doubtful virtue. After they departed in their turn the lady of the house immediately asked for payment, and Stonehouse discovered that he was missing his gold watch…

In February 1799 (just as Richard Horwood was putting the finishing touches to his map of the area, a side of bacon was stolen from Mr Crisp, cheesemonger, of 8 Cecil Court, by a fifteen year old boy called Edward Edwards. Richard Aldred, proprietor of the Bell, observed the theft and together the shopkeepers gave chase. The boy went on his knees in the snow and begged them not to call the watch as he had a bedridden father, but of course as one is reading a trial transcript the next step is predictable enough. Edwards was fined a shilling and confined two years in the House of Correction.

The popular image of Georgian justice is a harsh one, children sentenced to hang for stealing a pinchbeck buckle or a bun. The Westminster House of Correction was the notorious Bridewell, named for the Tudor Palace and illustrated by Hogarth in the Rake’s Progress. Edwards’ imprisonment seems harsh enough to modern eyes, but the jury had recommended mercy and the Houses of Correction were genuinely intended to inculcate reform through hard labour. One also feels for James Newby, transported to America with the prospect of approximately 14 years unpaid labour ahead of him. However, transportation was seen as a humane alternative to the death penalty, with at least the possibility of ‘reform’ and a fresh start. Life in Georgian London could be grim enough even for those who remained on the right side of the law, and what is most striking is not the harshness of the punishments but the number of acquittals. Although the number of capital offences rose dramatically during the eighteenth century through a series of so called Black Acts, with limited discretionary sentencing juries often proved reluctant to convict for minor offences even when the prisoners were palpably guilty – a factor seized on by early nineteenth-century reformers who were looking for practical reasons to cut the number of capital crimes beyond the purely humanitarian. And so, a stone’s throw from Seven Dials and the Rookeries of St Giles, the denizens of Cecil Court went about their business, murky and otherwise.

Famous Fizzogs

One of the Court’s most famous – albeit transient – residents was eight-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91), who visited London in 1764-5. During his stay in the city he met Karl Friedrich Abel and Johann Christian Bach and composed his first symphony. On arriving in London the Mozart family spent a single night at The White Bear in Piccadilly (now the site of the Criterion; this was quite usual for travellers arriving from the Continent), but between April 24th and August 6th 1764 they lodged with barber John Couzin in Cecil Court, paying twelve shillings a week for three rooms which were smaller than they might have wished, according to Leopold Mozart, and without cooking facilities so that all meals were brought in (John Jenkins, Mozart & the English Connection, 1998 p. 47). The family later moved from their Cecil Court lodgings to 21 Frith Street, Soho (then 15 Thrift Street). According to the edition of Mozart’s letters edited by Hans Mersmann, Leopold Mozart was absent for part of this time, convalescing at Dr Randall’s in Fivefields (Ebury Street) and Mr Williamson’s at 51 Frith Street. Evidently the family moved over to Frith Street to join him. (See also Otto Erich Deutsch: Mozart: A Documentary Biography. pp 32 and 34-36.) One can only speculate as to whether the sound of the child genius practising in Cecil Court ever disturbed or delighted his motley assortment of neighbours (whether or not it disturbed his father is a key issue, as we’ll see), but we do know that on April 27th and May 19th Wolfgang and his sister Nannerl set out from their Cecil Court lodgings to perform before King George III and Queen Charlotte.

Establishing the precise location of where Couzin (also spelled Cousins, Couzens and every variant thereof) lived with his own young family is trickier than one might suppose. The shops and mansion flats which now stand in Cecil Court date to the early 1890s. Two watercolours made just before the street was demolished are a surviving visual record of the buildings of Mozart's day, but there is no trace of their fabric. We do have an accurate map, showing building numbers, but although numbering began in London in the 1760s house numbers were not used in parish records until much later (in Cecil Court’s case the 1840s). Contemporary sources therefore only name the street, on the assumption that on reaching the Court one would have no difficulty in finding Mr Couzin’s premises – especially true if a red and white barber’s pole was displayed outside. For example, a June 1764 advertisement in the London Gazette for a concert at Spring Garden (St James’s Park) informs the reader as follows: “tickets at half a guinea each; to be had of Mr Mozart, Mr Couzin’s, Hair Cutter, in Cecil Court”. (It is worth noting that in the same advertisement Leopold gave the ages of his children as 11 and 7 rather than 13 and 9, shaving a couple of years off his prodigies to make them seem more extraordinary still; but then, the tour was an entirely commercial venture.) Otto Deutsch seems to have been the first to specify number 19, fully two centuries after the event and without identifying his sources. More recently Iwo and Pamela Zaluski mention that “the site of Mr Couzin’s is traditionally recognized as where Nos 19-21 now stand” (Mozart’s Europe: the early journeys, (1993), p. 127). It is possible that an oral tradition survived the re-alignment and rebuilding of Cecil Court in the early 1890s, but did it also survive the re-numbering which took place at the same time?

The answer is no, but the reference to numbers 19-21 does suggest that a memory of Mozart’s stay persisted. It has been possible to establish that John Couzin rented number 21, but that is 21 as the street was originally numbered, which stands on the site of today’s number 9 (although because the Court has been realigned the shop frontage of Mozart’s day is now in the open street).

Fortunately we have two tools at our disposal: the parish rate books (Cecil Court fell under Bedfordbury Ward, St Martin’s Parish; rates were collected annually for cleaning and paving) and Richard Horwood’s map, which reveals the numbering system in use in the eighteenth-century – and how it differs from today. Couzin arrived in Cecil Court in 1762, and remained until 1776 (1777 is missing, and he was gone by 1778). During all this time his position in the rate books remains constant, three inhabitants away from what is simply marked ‘Lane’ in early volumes, and which from 1774 is specified as St Martin’s Lane. There seems little doubt, then, that Couzin was at the eastern, St Martin’s Lane end of Cecil Court. There is remarkable continuity too in the order of the other names in the rate books over a long period. The collectors followed a routine, entering Cecil Court from St Martin’s Lane every year and walking along the north side of the street before crossing over and walking back along the south, ending at St Martin’s Lane again. This route isn’t specified in the 1760s but the north/south differentiation is made explicit in the 1790s, and makes perfect sense as it follows the numbering system on Horwood’s map: Horwood shows 24 numbered buildings, beginning with number 1 in the north eastern corner, crossing the Court at 12/13 at the Castle Street (now Charing Cross Road) end and finishing at 24 on the south side adjacent to St Martin’s Lane. Matching names to numbers, Couzin was at number 21. Where is that today?

The plans for the re-alignment of Cecil Court, as agreed in 1889, are held at Westminster City Archives. Essentially, the line of Cecil Court was straightened and moved several yards to the south. The old northern frontages are now underneath the shops on the north side of the street, and the original southern shop fronts are beneath the middle of the open Court today. By laying three antique maps on top of one another (Horwood’s eighteenth-century map as the base map, lined up with the 1889 plan for realigning the street, and with the 1894 Ordnance Survey laid on top of that) we can be certain that Number 21, as Mozart would have known it, is in the vicinity of the modern number 9. The threshold lies under the open street, walked over by hundreds of unsuspecting people every day, and the back of Couzin’s shop was directly beneath the front on number 9, now Mark Sullivan Antiques.

The location becomes of great importance if, as is highly likely, something of real note happened during Mozart’s stay. The distinguished musicologist and Mozart scholar, the late Stanley Sadie, argues convincingly that Mozart’s first symphonies were actually composed in Cecil Court and not in the stretch of Ebury Street (then Fivefields Row, now Mozart Terrace, just to keep things simple) where Mozart is commemorated with a plaque and a statue. In his biography (Mozart, the early years 1756-1781 (2006), pp. 64-65) he writes:

“It is usually supposed that it was during the time at Ebury Row that Mozart composed his first symphonies and perhaps the keyboard pieces in the so-called London Sketchbook. That does not square with the facts about Leopold’s illness and Nannerl’s oft-quoted accounts: “In London, when our father lay ill and close to death we were not allowed to touch the clavier. So, to occupy himself, Mozart composed his first symphony, with all the instruments, above all with trumpets and drums. I had to sit by him and copy it out …” [This is often assumed to have happened in Chelsea, some time after August 5th] By the time the family were in Chelsea … Leopold was recovered and there was no need for silence; clearly the symphony had been composed in Cecil Court”

Charles Burney, the composer and music historian, visited the Mozart family in Cecil Court. The boy was put through his paces for the distinguished visitor and Burney recorded his extraordinary musical abilities in considerable detail - playing, composing, and singing - before observing “after which he played at marbles in the true childish way of one who knows nothing”. (David Cairns: Mozart and his operas (2006) p. 17.) In June 1765, midway through Mozart’s stay in Cecil Court, the antiquary and naturalist Daines Barrington took Burney's approach a step further. In a spirit of scientific enquiry he attempted to analyse the nature of genius by examining Mozart musically (observing in details a similar sequence of performances to that described by Burney) but also, to a degree, psychologically: an early attempt at psychological profiling. His detailed report was published by the Royal Society in 1770. Although historian Hermann Abert dates this visit to June 1764, which would have been shortly after Burney’s and taken place while the family were still in Cecil Court, it appears to be a simple error as in Barrington’s original account he specifies June 1765, by which time they were in Soho. (Hermann Abert: W.A. Mozart (2007) p.44; Philosophical Transactions vol. LX, pp. 54-64, and ODNB.) It’s still worthy of note in this context, however, as it shows that Burney’s visit was not unique, and it gives an insight into the kind of visitors the family may have received in Cecil Court. With the right credentials, or perhaps for the appropriate consideration, one could evidently secure a private performance. The Cecil Court premises were more than a lodging house and ticket booth.

In summary then, as the site of the Mozart family’s first London address, 9 Cecil Court was where people came to buy tickets for the first concerts in the capital; it was where Mozart was living at the time he performed for the royal family and where scholars came to examine the child prodigy, and it is a strong contender for the location where he wrote his first symphony.

Another noteworthy inhabitant was the engraver Abraham Raimbach born in 1776 in Cecil Court to a Swiss father and English mother. (see Macmichael, J. Holden: ‘The Story of Charing Cross and its Environs’, 1906, p. 190.) He is best remembered for his collaboration with the artist Sir David Wilkie, engraving "The Village Politicians" (1814), "Blind Man's Buff" (1822) and other paintings of Wilkie’s, which brought him public recognition and financial security.

Snuff, Smut & Sedition

The earliest evidence for bookselling in Cecil Court to come to light so far is Huguenot and Jacobite, with a dash of smut. In 1704 an edition of J.F. Ostervald’s “Catechisme ou instruction dans la Religion Chretienne”, possibly printed in the protestant stronghold of Neuchatel was offered for the London market by Noe’ Bouquet “libraire, a l’enseigne de la Bible dans Cecil Court”. Our first Cecil Court bookseller. In 1717 and 1718 his widow, “la veuve Bouquet” sold at least two pamphlets by the French protestant exile (and minister at the Savoy) Jean-Armand Durbourdieu and an edition of C. Pegorier’s “Maximes sur la Religion Chretienne”. It’s not astonishing to find Huguenots in the Leicester Fields area – they founded the Orange Street Chapel in 1693 – and I suspect that Mozart’s landlord, John Couzin, may also have had Huguenot connections, although as yet I haven’t been able to prove it.

An advertisement leaf at the back of the fairly innocuous “Bishop Burnet’s Travels through France, Italy and Switzerland” (London, T. Payne, 1750; copy in the Taylorian, Oxford) reveals that books were being sold through the agency of the Highlander and Dove, a Cecil Court snuff shop. Books, offered bound, included: ‘The Christians Magazine” (“a book every Family in the Nation ought to have”) the slightly bawdy “Matrimonial Ceremonies display’d” and “The Patriot’s Miscellany”, sold only at the Highlander: “Mind you have the Scotch edition … warranted compleat and uncastrated, containing all those [matters] relating to the Stuart family … &c &c”; this is controversial stuff, suggesting that a mere five years after the ’45 Rebellion the flame of Jacobitism was still flickering in Cecil Court – dangerously close to the seat of Hannoverian power. They were also the London stockists of a 1749 Edinburgh edition of “Killing no murder, proving ‘tis lawful and meritorious in the sight of God and man, to destroy, by any means, tyrants, of all degrees”; originally directed against Oliver Cromwell, a 1708 edition was re-addressed to the French King and an Edinburgh edition was “reprinted for the heirs of Junius Brutus in that memorable year, 1745” with the subtitle “a discourse proving it lawful to kill tyrannical emperors, kings and all tyrants whatsoever”. The subtext is unmistakable.

While there’s no reason why a small snuff shop in Cecil Court should crop up all that often in the historical record, it may therefore not be a coincidence that only a couple of other references to their bookselling activities have come to light. ESTC throws up a 1748 edition of Henry ‘Namby Pamby’ Carey’s “Cupid and Hymen: a voyage to the isles of love and matrimony” and in 1749 the Cecil Court snuff shop was also listed as one of the places selling “Satan’s Harvest Home”, a pamphlet which is so vehemently anti-homosexual that one wonders if it written with a satirical edge, and is left with a residual suspicion that detailed accounts of sodomy, effeminacy and lesbianism might have had more to do with titillation than morality for many contemporary readers. The pamphlet became a best-seller. Refugee and niche-interest booksellers became of feature of Cecil Court again in the twentieth century: perhaps the Bouquets and the owners of the Highlander and Dove were the first in a long line.

Another early example of Cecil Court bookselling is also highly specialist – in this case Masonic. ‘Brother’ Dixon, one of the sellers of “A sermon, preached … before the ancient and honourable fraternity of free and accepted Masons” in 1772 was Robert Dixon, of 10 Cecil Court (old-style numbering, according to the ratebook for that year). ESTC does not throw up any other titles sold by Dixon, so presumably this was a one-off venture and Dixon was not an active bookseller.

Suspected Jacobites weren’t the only subversive presence in eighteenth century Cecil Court. Evidence is scanty and somewhat slanted, but we know that in 1795 the Angel in Cecil Court was one of the public houses which approached the London Corresponding Society asking to host a division. The radicalism of the LCS seems pretty moderate today – it sought parliamentary reform and the extension of the franchise – but in the tense atmosphere of the 1790s the government response, especially the new Gagging Acts, was uncompromising and effective.

In his pamphlet ‘The Rise and Dissolution of the Infidel Societies in This Metropolis’ (London, 1800), William Hamilton Reid (a bookseller and former radical, alarmed, like so many of his contemporaries, by the way in which events had unfolded across the Channel) describes an ‘atheist’ debating society which met at the Angel pub in Cecil Court later in the 1790s. Many leading LCS members were deists (not atheists, necessarily, in the modern sense of the word) and there was almost certainly considerable cross-over between the two groups.

Unlike private debating clubs where new members had to be approved and speeches were often prepared beforehand, such as those attended by Burke, Pitt, Boswell and Goldsmith earlier in the century, public debating societies were open to all who paid the weekly entrance fee and anyone could stand up and speak, frequently expressing political and religious ideas which were far from orthodox. (See Mary Thale: ‘London Debating Societies in the 1790s’, Historical Journal 32, 1, pp. 57-86.) Regarding them as potentially dangerous and a cause of unrest, the government clamped down hard towards the end of the decade. According to Reid there were two such societies in the West End, one on Wells Street and one on Cecil Court; the Wells Street society finished its business earlier and some of its members then made their way across town so that “some of the speakers contrived to exhibit at two places on the same night”. Reid continues:

“The Wells-Street Society being dissolved, in consequence of some disagreement among the members, the whole focus of Deism and Atheism was concentrated at the Angel, in Cecil-Court, St Martin's Lane, where a mingled display of real talent and miserable imitation was continued, on the Sunday and Wednesday evenings, till February, 1798; when, without any previous notice from the Westminster-magistrates, as had been customary in the city, a period was put to this promising school; the whole of the members and other present, being apprehended, and, the next day, obliged to find sureties for their appearance, to answer any complaint, at the next Quarter-Session, at Guildhall, Westminster; but no bill being found, the business ended with the withdrawing of the recognizances of the parties, 58 in number; which would certainly have been doubled, if the police-officers, sent to apprehend the club, had stayed till the business of the evening had commenced. This meeting was then deemed wholly political, an idea which could have no other foundation than the silly appellation of citizen, made use of by the members; or the circumstance of its being attended by John Binns, who was apprehended about the same period this society was disturbed, in company with Arthur O'Connor, in Kent. This unexpected stroke of justice, however, put the last hand to the Sunday-night meetings at the west end of the town; the associators in that quarter, after holding a few thin sittings, at a house near Compton-Street, Soho, being completely dispersed.”

Binns was a leading LCS member, but he wasn’t the only one: the contemporary account in the Gentleman’s Magazine reports that the meeting was “entirely composed of mechanics, mostly shoe-makers and taylors” with the exception of one “W. Hamilton Reid, professing himself a translator of languages”; a former member of the London Corresponding Society himself, Reid too is a link between the two groups.

The Gentleman’s Magazine also reported that “the landlord was obliged to find extraordinary sureties, and informed that the license of that house should certainly be withheld in future”. However, the Angel survived and crops up once more with a radical connection, this time during the treason trial of Colonel Despard in 1803.

Despard was another former member of the London Corresponding Society, which he joined after a spell in debtor’s prison; he had fallen on hard times after his recall from Honduras, where as Superintendent of the fledgling British colony his enlightened views on equal rights for freed black slaves had earned him the enmity of other British settlers, a fairly tough crew of logwood cutters. Despard was imprisoned – but never charged – on suspicion of involvement with the Irish Rebellion and then, in 1802, was accused by government informers of masterminding a wild scheme to capture the Tower of London and the Bank of England, and to assassinate George III. He was the last person sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered, an unfortunate distinction commuted to the less elaborate (but equally final) hanging and beheading. And Cecil Court’s role in all this? According to the evidence of John Emblin, a watchmaker of Vauxhall (cross-examined by no less a figure than William Garrow) a co-conspirator called William Landor claimed that while the rebel army marched on the Bank of England, the Tower and St James’s Palace bearing arms captured from the East India Company, the Angel would have served as a rebel HQ, where he would have received and sifted reports from “couriers and aid de camps”. It’s an extraordinary picture, and if the plot had been real (and less desperate …) the site of Cecil Court’s radical pub might have become every bit as worthy of a commemorative plaque as the site of the barber’s shop where Mozart stayed.

Misery, Murder, Movies – Flicker Alley Rises from the Rubble

Cecil Court was rebuilt at the peak of the political career of Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, the third Marquess of Salisbury, who was Prime Minister 1886-1892 and again from 1895 until 1902. Doubtless he saw the clearance of the old buildings as a great improvement and the shops and mansion flats which replaced them are attractively proportioned and sturdily built. Agreements with his contractors, Henry Daniel Davies and John and Benjamin Grover, date back to the mid 1880s and Salisbury may have been contemplating a redevelopment of Cecil Court to complement the construction of Charing Cross Road – much of the area was redeveloped around this time. However, he was overtaken by events.

Politics certainly played a leading part in the demolition of the original buildings, as the Liberal press sought to make political capital out of the supposedly wretched state of the Tory Prime Minister’s ‘slums’, a mere stone’s throw from Parliament itself. On October 1st 1888, under the headline “The Premier’s Rookeries Fall”, The Star thundered: “The roof of one of Lord Salisbury's rookeries, in Cecil-court, St. Martin's-lane, has given way. We recently described the delapidated and dangerous condition of his lordship's property, which he still refuses to repair, and leaves it an eyesore to the district and a disgrace to the metropolis. The houses in Cecil-court, which were long since ordered to be closed by the parish authorities, are now giving way all round. The court itself is now shut, and the public have to pay two policemen to keep people away from the property of the Prime Minister of England in case it should fall on their heads. But, then, there is no scarcity of policemen for West-end work. It is in the East they are needed, and are not there.” The story crossed the Atlantic where the ‘scandal’ was picked up by the New York Times (October 23rd 1888): “The dilapidated, rickety, unsanitary tenements in Cecil-court have at last reached such a stage of decay that they can hold together no longer … When a few more formalities have been gone through what is left of the wretched structures will be demolished by the Board of Works. A pretty state of things this, truly, on the estate of the Prime Minister of England, and a leading authority on the housing of the poor!”

Part of the background to all this was the hysteria surrounding the Ripper murders (The Star’s report appeared on the day following the discovery of two of the victims, Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes): Policemen were needed in the East End, not stationed at either of Cecil Court to stop the PM’s property falling on people. But just how rickety was Cecil Court at the time? Another figure pacing the streets of London in the late 1880s with an entirely less sinister purpose was the philanthropist Charles Booth, preparing his famous ‘poverty maps’ - large-scale surveys in which the wealthy were differentiated from the ‘very poor’ and ‘semi-criminal’ by careful colour coding. His original notebooksare held by the LSE, and he describes the two neighbouring Courts (in B354 p. 185) as follows: St Martin’s Court had “residential chambers inhabited by all sorts. Respectable otherwise. Shops below. The same with Cecil Court all red rather than the purple …” Red was the colour Booth used for ‘comfortable’ whereas purple denoted ‘poor & comfortable’. There were probably worse places to live than Cecil Court.

Historian Anthony Wohl makes explicit reference to the Star’s article and the motivation for it in his 1977 book ‘The Eternal Slum’: “Salisbury was a ground landlord in Cecil Court, a slum off St Martin's Lane, and some years later [ie in various articles May-September 1888] the Star, which had replaced Reynolds' and the Daily News as the most influential Liberal paper, tried to discredit the tory leader at a time when ground landlords were attracting attention.” In the 1870s the concentration of property ownership in a few hands peaked, and one could argue that the British Isles were more greatly affected than the rest of Europe. Radical voices charged wealthy landowners like Salisbury with driving rural labourers into the cities and housing them in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions when they got there. Housing became a live political issue in October 1883. Agents acting for the key players, Joseph Chamberlain and Salisbury, investigated each other (employment conditions for Chamberlain’s factory workers vs. housing conditions for Salisbury’s tenants) but found nothing discreditable. In his 1994 biography of Chamberlain Peter Marsh suggests that Salisbury always maintained the edge in the argument – for example, he was first to appreciate that overcrowding was an issue, not just poor sanitation (pp. 168-9). Be that as it may, Cecil Court had become a liability in its present form and the ‘Agreement concerning the realignment of Cecil Court between Charing Cross Road and St Martins Lane’ held by Westminster Archives is dated May 8th 1889.

Amongst the first tenants of the new buildings, completed in 1894, were early film distributors, publishers of promotional material and trade journals such as the Bioscope Annual and suppliers of technical equipment (though peppered with other businesses: a naval and military tailor at number 24; an artificial florist; an ostrich feather manufacturer). However, it was Cecil Court’s central role in the burgeoning British film industry inspired the nickname Flicker Alley. The searchable database produced by the London Project, a major study of the film business in London, 1894-1914, organised by the AHRB Centre for British Film and Television Studies, throws up over forty entries for Cecil Court. “Cecil Court and the Emergence of the British Film Industry” is the title of an article by Simon Brown in issue 10 the journal Film Studies.

Target printed by Graham & Latham of 20-22 Cecil Court c. 1910. The company manufactured and supplied cinema equipment and rifle ranges - a seemingly bizarre combination - but their 1909 advertisement in The Bioscope (a periodical of the early film trade quoted on the London Project website) makes all plain: ‘Electric Targets and Jungle Apparatus when worked in conjunction with Picture Shows provide an extra attraction and will double your income. Use up your basements and spare grounds’. Whether Graham & Latham followed their own advice, so that the whirr of a projector and crack of rifles alternated in the basement of 20-22 itself is not known, but this particular target has been used and kept as a souvenir. The company moved to 104 Victoria St, March 1911

Simon Brown appears to be the first to critically examine “the legendary heart of the early Industry” and ask “how […] could one street in London occupy such an iconic place?” Cecil Court is associated with some of the most important names in early cinema: Gaumont, Hepworth, Nordisk, Williamson, Globe, Tyler and Vitagraph had offices here, and the Cecil Court’s “importance has been frequently cited by pioneer filmmakers and historians alike”. Brown stresses the importance of the regional film trade, notes that many older companies which began to cater for the needs of the new industry were already too large for the units on Cecil Court and never came (the size of the shops also led to a fairly rapid turnover of tenants on the street as they outgrew their premises) and he suggests that the recollections of some of the pioneer filmmakers themselves were rose-tinted, motivated by a desire to present themselves as gentlemanly amateurs. However, Brown also argues that Cecil Court saw the first concentration of film-related businesses, and what’s more they were almost exclusively new businesses, bringing new skills to the industry and sharing “information, products, resources and clientele” (for example, sharing the costs of transporting the film reels themselves and offering joint screenings to the showmen who hired them). The earlier businesses tended to be one-stop shops - filmmakers and dealers in films and equipment. From 1907 the ‘new wave’ of businesses were often more specialised: dealers in the import and distribution of foreign films, or specialists in film rental or equipment alone. Brown concludes that Cecil Court

“was the heart of what was new in the British film industry, attracting young companies who clustered together to learn from one another. The history of early British cinema has for too long been couched in terms of failure … Although British film production undoubtedly ran into serious problems around 1909, the wider film industry was vibrant, diversifying, expanding, and spawning new and very different trades and companies year by year. Far from being the quaint home of the gentleman pioneers, it was to this industry that Flicker Alley was home.”

One can certainly detect the self-deprecating ‘amateurish’ tone identified by Brown, even in early accounts. For example, in 1936 Cecil Hepworth addressed a meeting of the British Kinematograph Society:

“Next, I opened a shop in Cecil Court to sell plates and cameras—I never did sell any —opposite to one which had just been opened by young Bromhead in the name of Leon Gaumont of Paris. While I was sitting there at the receipt of custom which never came, I designed a lantern with a cinematograph attachment for the showing of occasional films—the lantern lens and the film machine were slung on a pivot so that they could be interchanged in an instant. I bought the film machine from Bonn for a pound, and half a dozen forty-foot films- out of Paul’s junk basket for five bob apiece. With those six films, a couple of hundred lantern slides of my own making, two cylinders of gas and a lot more much cheaper gas of my own, I toured the country with an early cinematograph show.”

Steel fire door in the basement of number 27, c. 1912

We have no photographic record of the street at this time. The door in the basement of number 27 illustrated here is no ordinary door, but a solid steel fire door, a reminder of the highly flammable nature of early film stock and one of the last surviving physical links with the film trade. Such was the fear of fire that questions were asked in Parliament. Following a fire at the Globe Film Company in May 1911 Winston Churchill, then Home Secretary, assured the House that the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery were in no danger from their proximity to Cecil Court. One or two other relics of the period survive. Number 27 was home to the Pioneer Film Company Ltd circa 1912-1915 and a brass ash tray from the same period advertises them as “the house for up-to-date exclusive comedies”. Cecil Hepworth’s 1951 autobiography “Came the Dawn” is a partial but useful source. In 1903 Hepworth released the first ever film version of Alice in Wonderland from his offices at 17 Cecil Court.

Later in the century Cecil Court’s links with the film industry were more directly concerned with what went on in front of the camera. In the controversial 1961 film “Victim”, starring Dirk Bogarde and Sylvia Syms (the first British film to discuss homosexuality sympathetically and openly) Norman Bird plays the character of a Cecil Court bookseller, ‘Harold Doe’, who has fallen prey to the blackmailers. In the 1979 espionage thriller “The Human Factor” (based on the novel by Graham Greene, a regular visitor to the street) Nicol Williamson's contact is 'Halliday and Son, Antiquarian Books' at number 24. Unsurprisingly Cecil Court also featured in the 1987 film of the Helene Hanff novel ‘84 Charing Cross Road’ and more recently was one of the locations for the 2006 biopic ‘Miss Potter’, starring Renée Zellweger as the eponymous children’s author. In 1983 Cecil Court was the venue for the famous ‘Yellow Pages’ advertisement, in which Norman Lumsden appears as the elderly author searching for a copy of his own book, ‘Fly Fishing by J.R. Hartley’; the advert became so popular that the book was subsequently written and published.

Brass ash-tray made for the Pioneer Film Company, c. 1912

Booksellers’ Row

The Dome Postcard

Booksellers and publishers had already moved into the street before the First World War. Some were quite technical in nature and sat well alongside the early film pioneers. The Camera Club had premises on the corner of the street at the Charing Cross Road end from 1891 (a meeting is illustrated in a November 1895 issue of the Graphic), and enthusiasts were catered for by the Photographic News, published at 9 Cecil Court in the early 1900s. However, “The Dome”, a periodical devoted to literature and the arts which is closely identified with the aesthetic movement and the ‘nineties scene’, was published by the Unicorn Press at number 7 between 1897 and 1900. “The Dome” attempted to cover a broader range of verbal and visual art, music and theatre than either “The Yellow Book” or “The Savoy”, which were primarily literary periodicals. “The Dome” postcard shown here was illustrated by the famous wood-engraver Edward Gordon Craig and the book, Windjammers and Sea Tramps, by former merchant seaman and shipowner Walter Runciman (1902), is illustrated as another example of Unicorn Press printing.

One of the employees of Ernest Oldmeadow at the Unicorn Press, circa 1901-1902, was 18 year old Arthur Ransome, the future children’s author and spy (he was to write ‘Swallows and Amazons’ and marry Trotsky’s secretary). In his autobiography (published posthumously in 1976) Ransome describes turn-of-the century Cecil Court at some length (pp. 74-76) as it was where he used to spend his lunch hours, browsing in the bookshops, during his brief period of employment as a publisher’s office boy on neighbouring Leicester Square. One day, in the window of the Unicorn Press, Ransome saw a notice saying that ‘An Assistant’ was wanted, and he was delighted to secure the job at £1 per week, more than double his previous salary but with fewer opportunities for advancement in the publishing world. He describes the Unicorn Press as being on “very thin financial ice” already, so that “the firm lived under an almost continual threat of disaster”, but Ransome himself “had ample time for reading and writing” and he made all the use of it he could, honing his skills as an author and essayist. Oldmeadow, described by Ransome as “a short, stout, beady-eyed little man with an odd air of lay-brotherhood” went on to become “a wine-merchant, a writer of popular novels, a music-critic, a restaurant proprietor and, after conversion to Roman Catholicism, a successful and respected editor of the Tablet.”

An edition of William Beckford’s Vathek, published by Greening & Company in 1905

Cecil Court was also home to publishers Greening Ltd “whose main stock-in-trade was novels” according to Ransome, “some of which were described as ‘sensational’”. Ransome must also have been amongst the earliest customers of Watkins, the oldest esoteric bookshop in London, which arrived at number 21 in 1901. He describes a shop “devoted to theosophy, philosophy, spiritualism and kindred subjects” where he bought “a very well printed and edited American edition of Hume’s Essay on the Human Understanding which delighted me and continued to delight me for many years”.

Browsers outside the Stamp Shop at 6 Cecil Court in the 1940s

In 1904 William and Gilbert Foyle opened their first West End shop at number 16. After failing their Civil Service exams the brothers offered their old text books for sale and were so encouraged by the results that they opened a small shop in Peckham where they painted ‘With all faith” above the door. Cecil Court was the next step. David Low recounts the story in his autobiography “With All Faults”. Rent for the shop was £60 per year, but they were so successful that they were raided by Police (who suspected clandestine betting activities) and within a year were able to take on their first member of staff (who promptly disappeared with the weekly takings). Low records that they occasionally needed to borrow money from John Watkins to pay the wages, but by 1906 they were doing well enough to move to the famous premises on the Charing Cross Road.

Lawrence of Arabia made at least one recorded foray into Cecil Court. In the mid thirties artist Frederick Carter exhibited his works at the Basilica Gallery at number 6, and his portrait of Lawrence (which serves as frontispiece to a 1935 bibliography of his minor works by John Gawsworth) is dated from Cecil Court, March 1934. Carter (1883-1967) was a poet as well as artist and book illustrator with leanings towards mysticism and astrology. A friend of D.H. Lawrence he was also closely associated with figures such as Aleister Crowley, Arthur Machen, and Austin Osman Spare. Many of the leading occult figures of the day such as W.B. Yeats and Crowley were already customers of Watkins, which may go some way to explaining Carter’s association with the street. John Gawsworth was busily compiling collections of supernatural fiction at the time, which may have given him common ground with Carter, and he may have effected the introduction to Lawrence.

Gawsworth was the pseudonym of a very young T.I.F. Amstrong (1912-1970) who would find greater fame, with his friend Lawrence Durrell, as one of the ‘Cairo Poets’ during the Second World War. He published his bibliography shortly after Lawrence’s death in May 1935 and in the preface makes something of his ‘Holborn walks’ with ‘Shaw’ (one of Lawrence’s better known aliases). He had a facility for befriending older writers and was certainly known to Lawrence, who refers to him as a fellow ‘scribbler’ (T.E. Lawrence to his Biographers Robert Graves and Liddell Hart, 1963, p. 214; recounting his refusal to write a preface for Gawsworth’s edition of Wilfrid Ewart’s wartime diaries, published in 1937 under the title ‘Aspects of England’). It remains unclear whether Gawsworth introduced Lawrence to Carter, or whether the portrait (which must be among the last - of many, admittedly - made during Lawrence’s lifetime) was originally intended for publication in the bibliography.

Lawrence certainly frequented bookshops in the vicinity (he occasionally railed against bibliophiles, but the complex printing history he devised for the ‘Seven Pillars’ gives the lie to that) and could easily have encountered Carter on his own; for example, the two men shared a common admiration of DH Lawrence (Carter had already drawn DH Lawrence, and in 1932 had published “D.H. Lawrence and the Body Mystical”, detailing his association with the author). Perhaps one day the relevant letters will emerge.

Specialist foreign language bookshops have always found a home on the street. William Griffiths (1898-1962) opened a Welsh-language bookshop, Griffs, with his brothers in 1946 at number 4 (occasionally described as the ‘best bookshop in Wales’ despite its London location; see Antiquarian Book Monthly, vol. 27, 2000). Anton Powell (London Walks (1982) p. 54) mentions that the building had contained an air raid shelter during the war, and describes how friends and customers used up their allocations of rationed wood to build the shelves. Dylan Thomas was among the regular visitors.

In 1935 bookseller, publisher and translator Joan Gili (1907-1998) founded the Dolphin Bookshop at 5 Cecil Court, selling Spanish and Catalan books (the business transferred to Oxford in 1940 to escape the Blitz). With his English wife Elizabeth Gili was a founder of the Anglo-Catalan Society. According to his obituary in the Independent: “No 5 Cecil Court became such a centre for supporters of the Spanish Republic that in 1938 Joan Gili received threats from an official from the rival nationalist insurgent Spanish Embassy in London that his family in Barcelona would suffer if he did not rein in these activities.”

Typical of the output of the Dolphin Bookshop: selected poems of Federico Garcia Lorca, the left-wing poet shot by nationalist militia in the earliest days of the Spanish Civil War; this is a 1939 first edition of a translation by poet Sir Stephen Spender (who had himself served with the International Brigades in Spain) and by Gili himself. Demands made by the Spanish embassy that Gili should tone down his Republican sympathies had evidently fallen on deaf ears

In the 1930s Cecil Court became a well known meeting place for Jewish refugees, which in 1983-4 inspired R.B. Kitaj to paint Cecil Court W.C.2. (The Refugees), a work now in the Tate Collection. An online image is available. Cecil Court was one of Kitaj’s favourite haunts and the painting was born out of an increasing awareness of his own Jewish heritage. Kitaj himself is depicted reclining in the foreground, and to the left (holding flowers) is the Cecil Court refugee bookseller Ernest Seligmann, for whom he was a regular customer.

A more unfortunate incident worthy of brief mention is the Cecil Court antique shop murder. In March 1961 Elsie Batten, a 59 year old assistant in Louis Meier’s antique shop at 23 Cecil Court, was stabbed to death. Her murderer, Edwin Bush, was identified and caught within days following the circulation of Identikit pictures - the first case to be solved in the UK using the Identikit System, a significant advance in crime detection. Full details are available on the Metropolitan Police website.

Hambling’s catalogues, c. 1948 and 1968

Not all shops on the street were bookshops. Model railway enthusiasts may remember Hambling’s model shop, founded by radio ham and modeller A.W. Hambling, which came to 10 Cecil Court c. 1938 and specialized in miniature gauges. They manufactured their own range of kits and accessories as well as stocking famous brands. Mr John Shaw, who arrived at the shop in 1954 and spent most of his working life in Cecil Court, recalls that Mr Hambling was the creator of ‘00 Gauge’. His hobby was model railways, especially HO (half ‘O Gauge’) trains from the US and the Continent. The bodies of British-outline locomotives were too small for the motors (reflecting the loading gauge of the real thing) and Hambling enlarged them – creating 00. He made the first body tools for Hornby Dublo. His own tools were destroyed during the war when his workshop on Endell Street near the Opera House was bombed and although profits from his wartime manufacturing kept the business afloat it never quite recovered its pre-war level of innovation. Mr Shaw remembers that Hambling refused to have anything to do with plastic – even though most of the clientele were serious modellers who demanded the last word in accuracy (and plastic was cheaper). The shop moved across the street to the old LMS/BR Midland Region parcel offices (now part of Lipmans) in the 1970s, but closed after 47 years when faced with an impossible hike in rent.

Between 1963-1970 Mr Trevor Vincent-Edwards worked for Rays Agency at number 19, a curious survival from an earlier age which “only ever dealt in "Classified" advertisements. Situations Vacant, Cars for Sale, etc. They never charged clients a fee, but derived their income from the commission paid by the newspapers.” According to Mr Vincent-Edwards: “In the 1960's a working day at Rays Agency had probably changed very little since the agency was founded in 1921.”

The perspicacious reader will note that I have not written much about the booksellers who have made Cecil Court famous today. Names such as R.V. Tooley, H.M. Fletcher, Harold Mortlake, Harold Storey, bookseller and British Buddhist Harold Edwards, George Suckling, Robert Chris and David Low are renowned in the world of books and well within living memory. Did you work for them or were you a customer? Please get in touch with your anecdotal evidence!